Why Sustainable Bharat?

Motivating the need for India-based environmental entrepreneurship.

In this article, I motivate the purpose of this blog — developing business-based solutions to environmental issues in India. I first establish why solving environmental issues is critical, then explain why India should be the country to solve them, and finally illustrate why business is our best tool to solve them at scale.

Environment

Human activities — and the greenhouse gases (GHGs) they emit — have caused 1.1°C of surface temperature warming over pre-1900 levels. Of the 2400 gigatons of CO2 emitted since 1850, 42% was emitted between 1990 and 2019. Atmospheric concentrations of CO2, methane, and nitrous oxides have increased every year and are currently at their highest-ever levels. While the rate of emissions growth has slowed to 1.3% in the past decade, emissions levels continue to rise [1].

Global warming has already impacted planetary health.

Sea Levels — since 1901, global sea levels have risen by 0.2m. The rate of sea level rise has jumped from 1.3 mm/yr in 1901-1971 to 3.7 mm/yr in 2006-2018. 40% of the world’s population lives in areas at risk of sea level rise [2].

Extreme Events — the frequency of extreme events like heatwaves, heavy precipitation, drought, and tropical cyclones has increased. Additionally, compound extreme events — like concurrent heatwaves and droughts — have become more likely [1].

Water and Food — Half of the world’s population experiences severe water scarcity for some part of the year. While agricultural productivity has increased in the last 50 years, growth is slowing and will soon become negative. Food production from fisheries has also dropped as a result of ocean warming and acidification [1].

Human Health — increased heat stress has a direct effect on human health. However, human mortality and morbidity are also indirectly affected by a greater incidence of food-, water-, and vector-borne diseases. Mental health issues have also worsened as a result of trauma, culture loss, and displacement [1].

Settlements and Infrastructure — transportation, water, and energy systems have been compromised, both by extreme events and slow-onset events like land degradation and changing rainfall patterns. Damages are particularly severe in urban areas and climate-exposed sectors like agriculture and energy. Consequently, individuals have been affected through the destruction of homes and infrastructure and the loss of property and income [1].

Displacement — in the last decade, weather-related disasters have displaced 220 million people [3]. 32.6 million were displaced in 2022 alone [4]. Displacement has severe impacts on people and their livelihoods, often breeding more conflict in the areas that people move to.

In the coming years, decades, and centuries, each of these trends will intensify. Sea level rise will accelerate, extreme events will intensify, water and food insecurity will worsen, and impacts on human health, livelihoods, and settlements will be amplified. Outside of its direct effects, climate change is also a threat multiplier — it will exacerbate existing socioeconomic and geopolitical issues.

How do we deal with it? There are two broad categories of responses — mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation involves reducing the flow of GHGs into the atmosphere by reducing emissions and building carbon sinks. However, GHGs don’t disappear once they enter the atmosphere. CO2, for example, stays in the atmosphere for 300 to 1000 years [5]. Even if we stopped all emissions today, we would still be dealing with the effects of climate change for centuries because of the stock of GHGs in the atmosphere. Therefore, we also need adaptation measures — actions that reduce vulnerability to the current and expected impacts of climate change.

India

Climate change is an unequal issue, both in terms of its causes and effects. OECD countries account for 17% of the world’s population [6], but have contributed 50% of total GHG emissions to date [7]. While India accounts for a similar proportion (18%) of global population, it has contributed just 4.6% of total emissions. Despite India’s rapid economic growth, India only contributes 7% of annual global emissions, compared to 30% from OECD countries [7].

Despite relatively low emissions, India has and will continue to deal with the worst effects of climate change. India was ranked the 6th worst-affected country by climate change in 1993-2022. This is due to the 80,000 fatalities and $180 billion in economic losses caused by the 400 extreme weather events that occurred during this period, including floods, heat waves, cyclones, and drought [8]. Currently, 75% of Indian districts are extreme event hotspots, including 95% of coastal districts [9]. As climate change worsens, the frequency and intensity of these extreme events will continue to increase.

The catastrophic but sporadic effects of extreme events are complemented by gradual, broadly distributed risks from slow-onset warming and environmental degradation. 33% of India’s land is degraded or desertified [10]. Rising temperatures will contribute to lost outdoor working hours, putting 2.5-4.5% of GDP at risk [11]. Sea level rise will endanger the crores of Indians that live along the coast. Changing rainfall patterns and local climates will cause large declines in crop yields from rain-fed agriculture [12]. India also has major problems to contend with in terms of air and water pollution, waste management, food and water scarcity, urban planning and biodiversity loss.

A just solution to climate change would involve large amounts of funds flowing from the high-income countries that caused climate change to the low-income countries that are impacted by it. American climate policy and the consistently disappointing results from COP each year have shattered any illusions that this is realistic possibility. Therefore, we must take matters into our own hands. India cannot compromise on growth — economic growth has raised 250 million people out of poverty since 2005-06 and greatly improved standards of living nationally [13]. However, growth must be climate resilient. By developing and deploying adaptation measures while mitigating our emissions, India will be well-positioned to deal with the present and future impacts of climate change.

While the climate risks India faces are daunting, they also present opportunities. Just as the negative effects of climate change exacerbate each other, environmental solutions produce economy-wide multiplier effects. As a developing economy with both capital and technological capabilities, India can produce cost-effective climate solutions at scale. The government’s willingness to engage with climate issues and India’s growing geopolitical prominence have already made India a climate leader globally [14]. We can leverage these opportunities and influence to show the developing world how to deal with climate change without compromising on economic growth.

Business

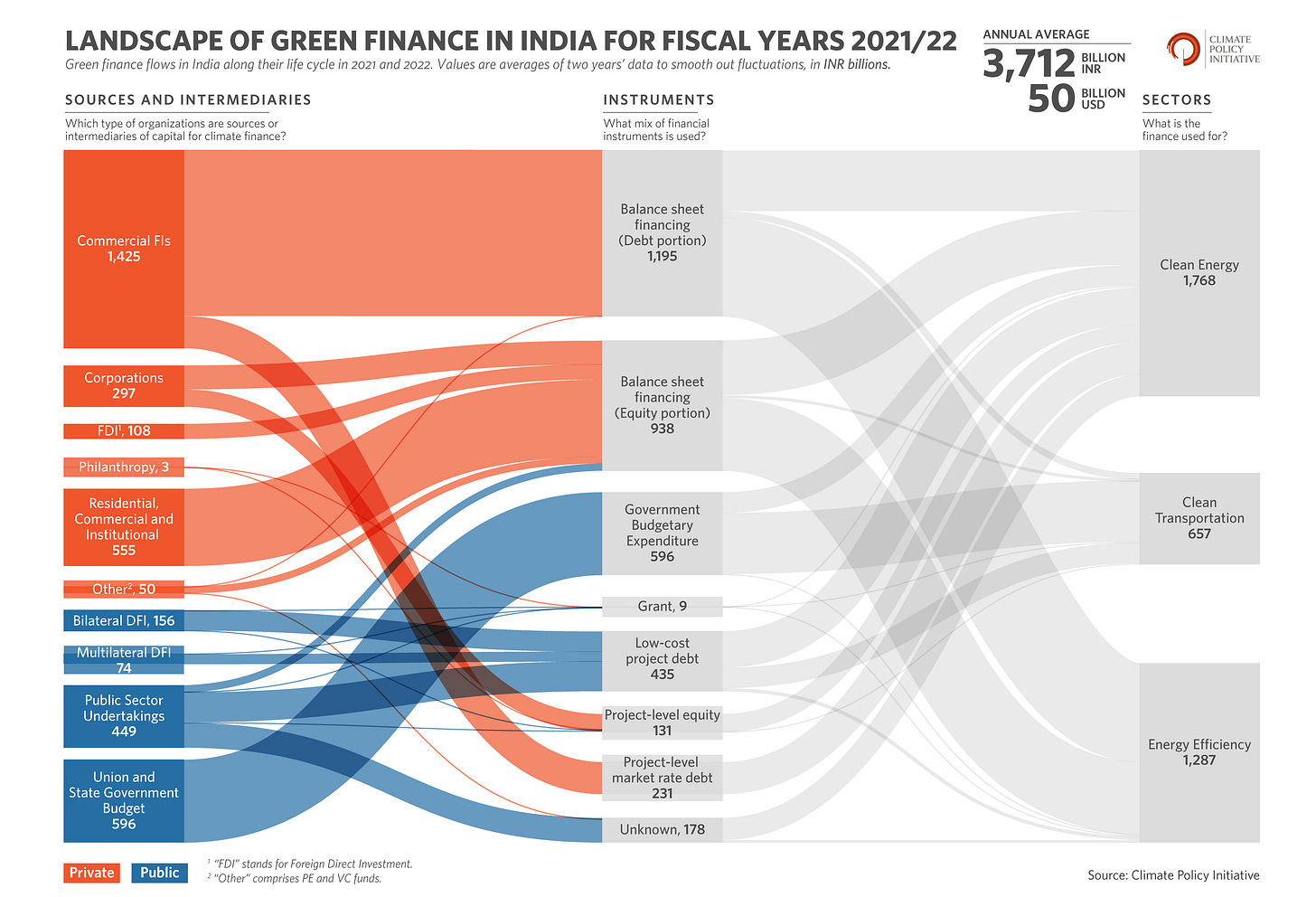

Climate change poses immense risks, but it is also a massive business opportunity. Global climate finance reached USD 1.46 trillion in 2022, and this is just a fraction of the USD 7.4 trillion required annually between now and 2030 [15]. 90% of this financing was for mitigation. Developed countries are ignoring mitigation investments because the near-term impacts of climate change are not as severe for them. While these investments are important, investing in adaptation measures is crucial for the 3.3 billion people that live in regions that are highly vulnerable to climate change [1]. However, adaptation investment only accounts for 5% of global climate finance. Within India, all climate finance goes toward mitigation — clean energy, clean transportation, and energy efficiency [16].

Adaptation investment is also needed to help individuals and producers in vulnerable sectors build climate resilience. Consumers need ways to deal with air pollution, plastic pollution, rising temperatures, and resource constraints. The agriculture sector is particularly critical — it employs 46% of India’s workforce, is responsible for the entire country’s food security, and is arguably the most vulnerable sector to climate change [17]. Global investments in these areas have been lacking because developed countries don’t face the same risks. Large emerging economies like India and China need to fill this gap — we have the ability, funds, and motivation to do so.

Unlike mitigation, where investment focuses solely on emissions reduction, India’s adaptation issues are complex and interconnected. Water scarcity affects agricultural output, which impacts food security and livelihoods. Rising temperatures increase energy demand for cooling, straining power grids and exacerbating air pollution from fossil fuel generation. Consequently, the benefits of adaptation investment in one area are often realized elsewhere. Therefore, businesses that develop integrated solutions are better-positioned to capture value.

For India to effectively adapt to climate change, businesses must move beyond viewing environmental challenges as compliance issues and instead recognize them as core business opportunities. The companies that will succeed are those that develop scalable solutions tailored to India’s specific environmental challenges. As economies of scale make these solutions affordable, Indian businesses can tap into demand from the billions of people across the developing world that have similar adaptation needs.

India has two options to deal with climate change. We can rely on the countries that caused climate change to provide the funding, technology, and solutions needed to solve it. Alternatively, we can turn it into an opportunity by developing and distributing environmental solutions to the entire developing world. Sustainable Bharat attempts to establish how to capitalize on this opportunity by understanding India’s environmental challenges, building management acumen, and studying companies in the environmental space.

Works Cited

[1] IPCC, “AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023,” Geneva, Switzerland, Summary for Policymakers, 2023. Accessed: Feb. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

[2] United Nations, “The Climate Crisis – A Race We Can Win.” Accessed: Feb. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.un.org/en/un75/climate-crisis-race-we-can-win

[3] USA for UNHCR, “How climate change impacts refugees and displaced communities.” Accessed: Feb. 14, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/how-climate-change-impacts-refugees-and-displaced-communities/

[4] J. Apap and S. J. Harju, “The Concept of ’Climate Refugee’: Towards a Possible Definition,” European Parliamentary Research Service, Oct. 2023. Available: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/698753/EPRS_BRI(2021)698753_EN.pdf

[5] NASA Science Editorial Team, “The Atmosphere: Getting a Handle on Carbon Dioxide.” Accessed: Feb. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://science.nasa.gov/earth/climate-change/greenhouse-gases/the-atmosphere-getting-a-handle-on-carbon-dioxide/

[6] OECD, “Population.” Accessed: Feb. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/population.html

[7] Climate Watch, “Historical GHG Emissions.” Accessed: Feb. 17, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ghg-emissions?breakBy=regions&calculation=CUMULATIVE&end_year=2022&gases=co2®ions=ANNEXI%2CNONANNEXI&source=PIK&start_year=1850

[8] L. Adil, D. Eckstein, V. Künzel, and L. Schäfer, “Climate Risk Index 2025,” Germanwatch, Feb. 2025. Available: https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/2025-02/Climate%20Risk%20Index%202025.pdf

[9] A. Mohanty and S. Wadhawan, “Mapping India’s Climate Vulnerability – A District Level Assessment,” Council on Energy, Environment and Water, New Delhi, Oct. 2021. Available: https://www.ceew.in/sites/default/files/ceew-study-on-climate-change-vulnerability-index-and-district-level-risk-assessment.pdf

[10] Indian Space Research Organization, “Desertification and Land Degradation Atlas of India,” Space Applications Centre, Jun. 2021. Available: https://vedas.sac.gov.in/static/atlas/dsm/DLD_Atlas_SAC_2021.pdf

[11] J. Woetzel et al., “Will India get too hot to work?” McKinsey Global Institute, Nov. 2020. Available: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/sustainability/our%20insights/will%20india%20get%20too%20hot%20to%20work/will-india-get%20too-hot-to-work-vf.pdf

[12] S. N. S. Tomar, “Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Accessed: Dec. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1909206

[13] R. Chand and Y. Suri, “Multidimensional Poverty in India since 2005-06,” NITI Aayog, New Delhi, Jan. 2024. Available: https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2024-01/MPI-22_NITI-Aayog20254.pdf

[14] “CCPI 2025: Ranking and Results.” Accessed: Mar. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ccpi.org/

[15] B. Naran, B. Buchner, M. Price, S. Stout, M. Taylor, and D. Zabeida, “Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2024: Insights for COP29,” Climate Policy Initiative, Oct. 2024. Accessed: Feb. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2024/

[16] M. Chakravarty, U. Pal, J. Kaur, A. K. Samal, A. Sikka, and V. Sen, “Landscape of Green Finance in India,” Climate Policy Initiative, Dec. 2024. Available: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Landscape-of-Green-Finance-in-India.pdf

[17] Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, “Periodic Labour Force Survey Annual Report,” Sep. 2024. Accessed: Dec. 11, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://dge.gov.in/dge/sites/default/files/2024-10/Annual_Report_Periodic_Labour_Force_Survey_23_24.pdf

Excellent article Karthik; packed with relevant facts. Like the call for action on home-grown innovation.

Loved the read!