The Outsiders

Eight Unconventional CEOs and Their Radically Rational Blueprint for Success.

Given access to the same resources and exposure to the same challenges as the rest of a group, a positive deviant is an individual that employs uncommon behaviors or strategies to find better solutions than their peers [1].

By definition, positive deviation will exist in any meaningful statistical distribution. However, if many positive deviants share characteristics, studying those characteristics can yield useful insights. As Warren Buffett puts it, “if you found any really extraordinary concentrations of success, you might want to see if you could identify concentrations of unusual characteristics that might be causal factors” [2].

The logic of this approach is compelling. However, it is rarely applied to business for two reasons. First, the managers that are typically studied are “celebrity” founders and CEOs with groundbreaking, transformative ideas — Jensen Huangs and Elon Musks. While studying these managers is important, it’s hard to learn from or replicate their success. Second, there isn’t a consensus measure of business success. In “The Outsiders”, William Thorndike Jr. attempts to fill this gap.

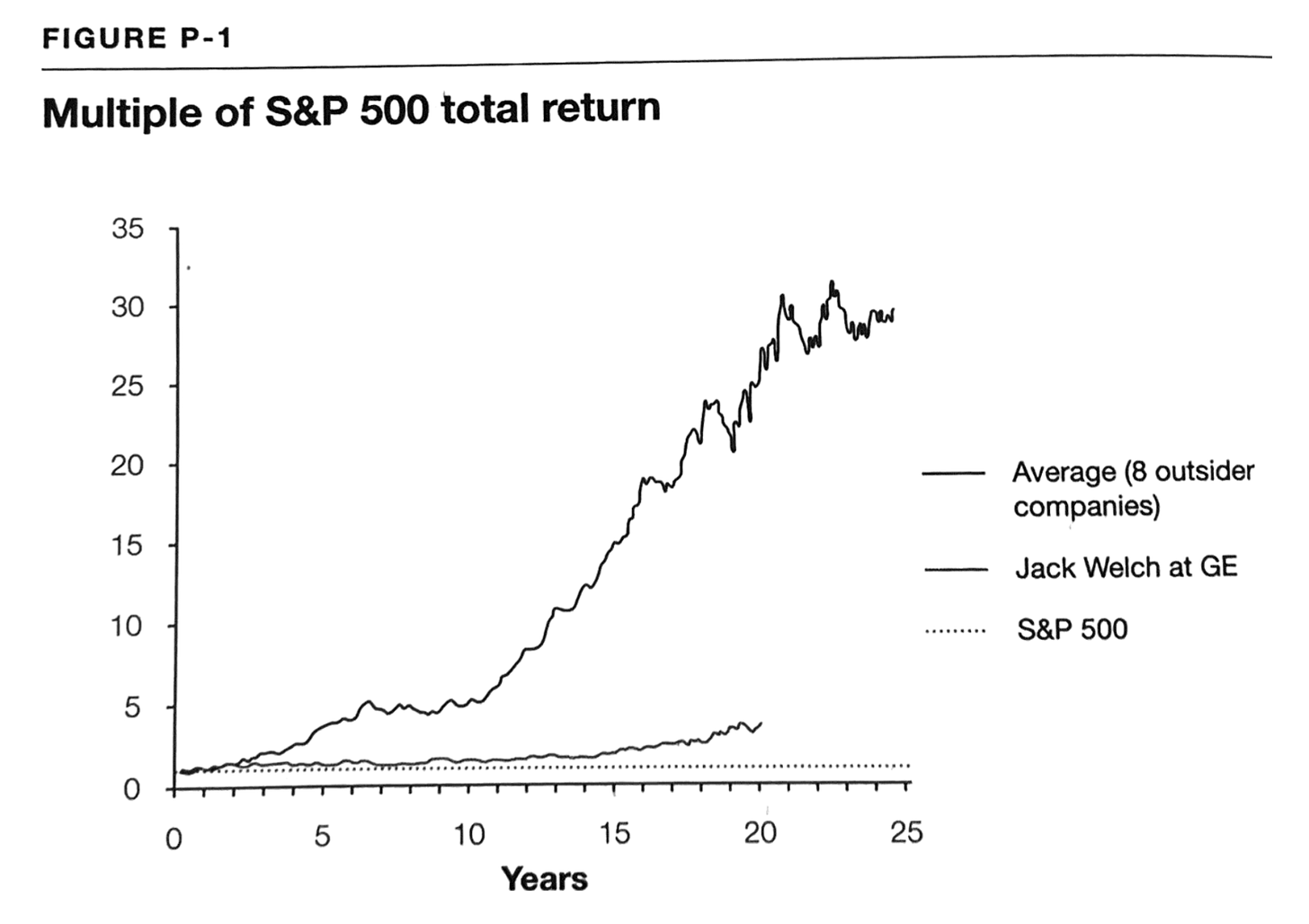

He argues that growth in per share value is the true measure of managerial success. Consequently, only three pieces of information are required to gauge a manager’s performance — the growth of per share value for the company, its peers, and the market during the manager’s tenure. Thorndike therefore defines a positive deviant as a manager at a firm where the increase in per share value during their tenure exceeded both peer companies and the S&P 500 by at least three times. Only eight CEOs in American history pass the test — Thorndike’s “Outsiders”. On average, these CEOs outperformed the S&P 500 by over twenty times and their peers by over seven times.

The Outsiders is the product of studying these eight CEOs, their companies, and their uncannily similar approaches to management. These eight case studies comprise the bulk of the book. Instead of attempting to summarize the case studies, this article will outline what Thorndike calls the Outsider worldview — a shared set of principles that guided their management.

Capital allocation is a CEO’s most important job.

A CEO has to do two things well to be successful — run operations efficiently and deploy the cash generated by those operations. However, most CEOs, and the books and institutions they learn from, focus primarily on operating. Conversely, Outsider CEOs focused on capital allocation — deploying capital generated by debt, equity, or internal cash flow to invest in existing operations, acquire other businesses, issue dividends, pay down debt, or repurchase stock.

In some cases — like with Capital Cities CEO Tom Murphy and his COO Dan Burke — Outsiders delegated all management of operations. “Burke, was responsible for the daily management of operations, and Murphy for acquisitions, capital allocation, and occasional interaction with Wall Street.” As Burke puts it, his “job was to create the free cash flow and Murphy’s was to spend it.”

What counts in the long-run is the increase in per share value, not overall growth or size.

Maximizing shareholder value follows naturally from the Outsiders’ investor-like focus on capital allocation. While this objective may seem obvious, managers often seek organizational size and growth, a sometimes conflicting goal. It is rare for a firm to shrink itself, even if it’s the right decision for shareholders. However, most Outsider CEOs shrank both their share bases and operations by repurchasing stock, selling assets, spinning-off companies, and eliminating underperforming divisions. None of these tools were new. However, the Outsiders used them to deliver value to shareholders and further strategic objectives, often ignoring the market imperative to grow larger.

In divesting noncore businesses, Bill Anders sold the majority of General Dynamics’ businesses within two years of taking over as CEO. At Ralston Purina, Bill Stiritz used spin-offs — separating a division or subsidiary into a new, independent company — aggressively to provide transparency to shareholders and keep the original company focused on core businesses. In 2000, he spun-off Energizer Holdings, which accounted for 15% of the company’s total value at the time.

Cash flow, not reported earnings, is what determines long-term value.

Outsider CEOs tended to reject the complexity of business and the noise generated by peers and analysts. Their focus on value and simplicity led them to reject Wall Street’s preferred metric — reported earnings — in favor of a single-minded pursuit of free cash flow. This was an iconoclastic objective at a time when most managers looked to maximize quarterly reported earnings to keep Wall Street happy.

The most extreme example of this is John Malone at TCI, who actually attempted to minimize reported earnings because it meant higher taxes. Instead, he funded internal growth and acquisitions with pretax cash flow. To fully measure the firm’s ability to generate cash, Malone introduced the term EBITDA. While EBITDA is the most enduring metric, other Outsider CEOs, including Henry Singleton at Teledyne, also created their own cash flow metrics to better guide their businesses.

Decentralized organizations release entrepreneurial energy and keep both costs and “rancor” down.

As Thorndike puts it, “There is a fundamental humility to decentralization, an admission that headquarters does not have all the answers and that much of the real value is created by local managers in the field.” In addition to devolving control to the people that actually interact with customers, decentralization reduces overhead and releases entrepreneurial energy.

Capital Cities was a highly decentralized organization — publishers and station managers commanded internal prestige and were responsible for all important decision-making. The few staff at headquarters primarily supported the managers of operating units. Combined with consistent investments in news talent and technology, this decentralization made almost every Capital Cities station a leader in its local market. Berkshire Hathaway provides another stark example of decentralization — there were 23 employees at headquarters in a company that employed 270,000. Warren Buffett puts it best — “hire well, manage little”.

Independent thinking is essential to long-term success, and interactions with outside advisers can be distracting and time-consuming.

Regular communication with Wall Street and the business press were seen as important CEO roles. Once again, the Outsiders rejected common practice, minimizing their outward-facing responsibilities. At Teledyne, Henry Singleton was nicknamed “The Sphinx” due to his reluctance to speak with analysts or journalists. Warren Buffett estimated that the average CEO spent 20% of their time communicating with Wall Street. Buffett spent no time with analysts, never attended investor conferences, and didn’t provide quarterly earnings guidance.

Additionally, Outsiders avoided relying on external advisers like consultants and analysts, typically making important decisions autonomously or with the help of a small group of trusted internal advisers. Despite delegating everything else, Buffett never delegated capital allocation decisions, doing all analytical work and investment negotiation on his own. Since he only bought companies in industries he knew well, he moved quickly, often making large investment and acquisition decisions in a few minutes. Similarly, John Malone at TCI handled the sale of his company to AT&T alone, often dealing with dozens of lawyers, bankers, and accountants on the other side.

Sometimes the best investment opportunity is your own stock.

While buybacks and stock-based compensation are now increasingly common, the Outsiders were pioneers in the frequency and size of their stock repurchases. Henry Singleton bought back 90% of shares outstanding at Teledyne, Bill Stiritz bought 60% at Ralston Purina, Katherine Graham bought 40% at Washington Post, and Bill Anders repurchased 30% of General Dynamics’ outstanding shares in a single transaction.

These buybacks were not indiscriminate — Outsiders repurchased when stock was trading at single-digit multiples and often used it to finance major investments when prices were high. This reflects the Outsiders’ investor mindset — if the firm’s stock is the highest-yield investment opportunity, repurchase. Effectively, buyback returns became a benchmark for other capital allocation decisions. For Bill Stiritz at Ralston Purina, “The hurdle we always used for investment decisions was the share repurchase return. If an acquisition, with some certainty, could beat that return, it was worth doing.”

With acquisitions, patience is a virtue, as is occasional boldness.

Some Outsiders were extremely acquisitive — John Malone averaged one acquisition each week between 1973 and 1989. However, their acquisition strategies were highly disciplined, often based on comparing acquisition returns to buyback returns or other investment opportunities. When asking prices were slightly higher than the Outsiders’ value estimates, they walked away. This discipline manifested in long waiting periods between acquisitions. Despite making frequent acquisitions for the rest of his career, Dick Smith at General Cinemas didn’t make any major acquisitions for a decade because he felt firms were overpriced.

Despite this discipline, the Outsiders were boldly opportunistic. When they liked a potential acquisition, they weren’t afraid to make massive bets. Dick Smith’s largest acquisition equalled 62% of General Cinemas value. For John Malone, the average annual value of acquisitions was 17% of TCI. Tom Murphy made multiple acquisitions that each exceeded 25% of Capital Cities’ enterprise value.

In “The Outsiders”, Thorndike highlights eight CEOs that were investors first and operators second. By delegating management of operations, they focused on their most essential responsibilities — minimizing the cost of capital and maximizing returns. This simplicity led them to make similar, unconventional choices that yielded immense results for their firms and shareholders. Critically, their success across a range of very different industries reflects the generalizable, fundamentally sound logic of the Outsider worldview.

Bibliography

[1] “What is Positive Deviance?” Accessed: Jan. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: positivedeviance.org

[2] W. E. Buffett, “The Superinvestors of Graham-and-Doddsville,” Hermes, the Columbia Business School Magazine, vol. Fall 1984, May 17, 1984. Available: csinvesting.org