Indian Agriculture and the FPO Model: Part 2

Understanding the FPO Model.

Part 1 of this series outlined the breadth and severity of challenges that India’s farmers face. In this article, I evaluate farmer collectivization as a potential solution to these challenges. First, I contextualize and define Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs). Second, I illustrate the policy landscape that FPOs currently inhabit. Finally, I evaluate FPO performance and compare FPOs to the Amul model to provide future insights.

Background

Farmer collectivization is a natural solution to the fractionalization of agricultural landholdings and the issues discussed in Part 1. The logic is simple — by coming together in large groups, farmers can benefit from increased efficiencies and economies of scale. Kanitkar [1] succinctly groups these benefits into four categories. First, input — cost of cultivation falls due to aggregated demand. Second, output — aggregating produce yields negotiating power and opportunities for value addition and market linkage. Third, throughput — by sharing knowledge and information about agricultural practices collectively, individual (and overall) farmer productivity will increase. Finally, reduced risk — farmers are better equipped to absorb individual shocks when supported by a collective.

The earliest farmer collectives in India were the credit cooperatives formed by the 1904 Credit Societies Act. The cooperative effort continued with the establishment of producer cooperatives — non-credit societies (1912) and multi-state cooperative societies (1942) — that have been periodically reformed. Today, 26,767 Agricultural and Allied Cooperatives and 1.03 lakh Primary Agriculture Credit Societies (PACS) include 98.4 lakh and 14 crore members respectively [2]. Despite their immense coverage, cooperatives have struggled to become effective, self-sustaining entities. After the globalization and liberalization of the 1990s, cooperatives continued to operate with substantial government funding, personnel, and influence [3]. This government control led to corruption, bureaucracy, and a lack of market orientation — cooperatives failed to remain competitive and integrate efficiently into markets [4]. For example, PACS would appear to cover India’s entire farmer population, but they accounted for just 18% of total agricultural credit in 2009, down from 56% in 1985-86 [5].

In response to these issues with cooperatives, Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs) were proposed in 2000 — a new, business-focused agricultural collective that would be independently managed by farmers without government ownership and influence [3]. Farmer Producer Organization (FPO) is a generic term used by the government to refer to both cooperatives and producer companies. Although the title mentions FPOs to stay consistent with government schemes and other research, FPCs are the focus of this article.

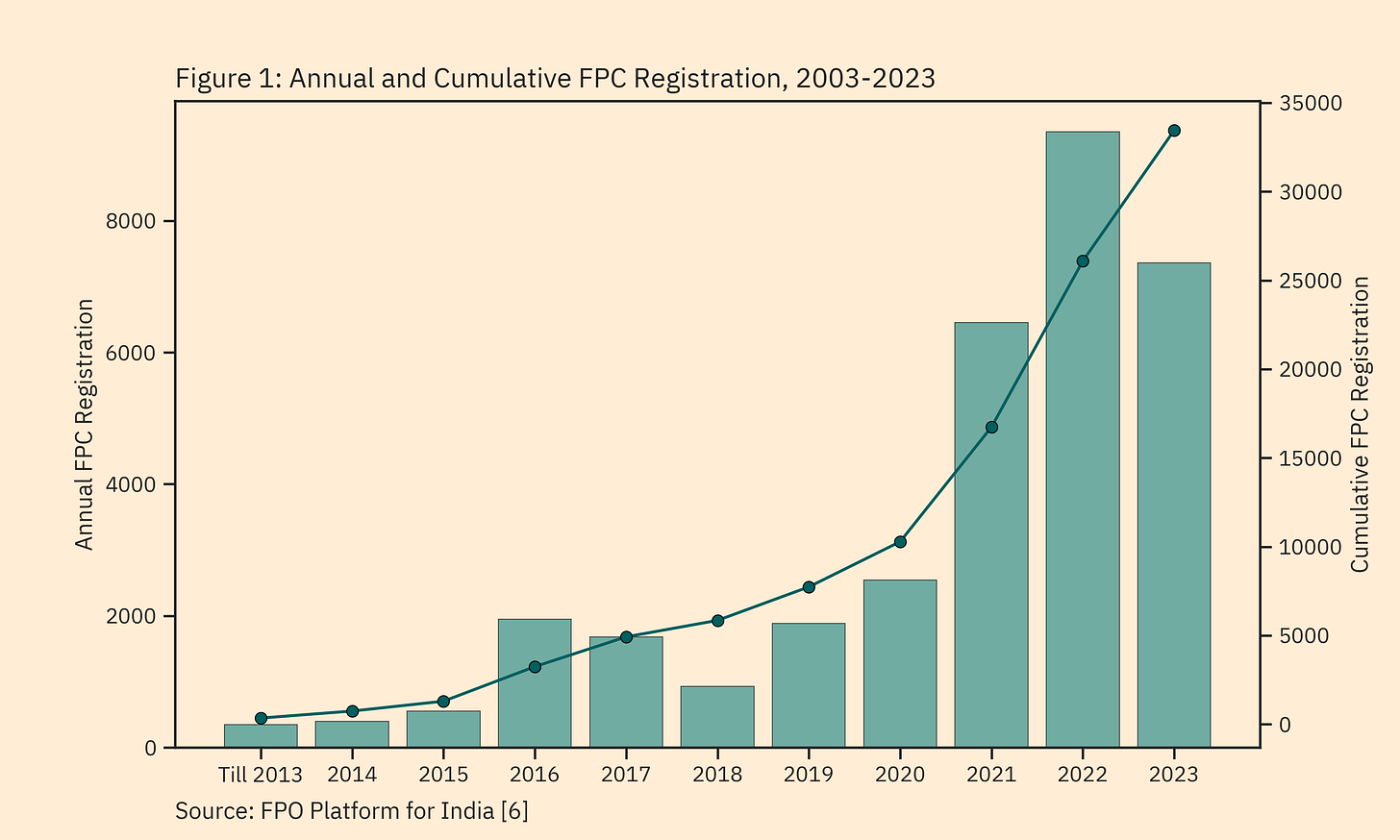

The Companies Act was amended in 2005 to legalize the establishment of FPCs. Despite initially negligible FPC registration, Figure 1 displays a huge acceleration in the last decade. Today, 33711 FPCs [6] are estimated to include 10-20% of India’s farmers as members [7].

Policy Framework

The explosion of FPO registration in the last decade was catalyzed by NABARD’s PRODUCE fund, announced in 2014-15 [8]. However, the vast majority of FPOs have been formed since PM Modi’s announcement of the 10,000 FPO Scheme in 2020 [9].

Under the scheme, the Department of Agriculture, Cooperation, and Farmers’ Welfare designates Implementing Agencies (IAs), like NABARD (National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development) and SFAC (Small Farmers’ Agri-Business Consortium). State agencies can also apply to be recognized as IAs. These IAs are responsible for engaging Cluster-Based Business Organizations (CBBOs). CBBOs are entities that form and promote multiple FPOs at a state or cluster level, working with them for a 5-year “handholding period”. These CBBOs must have expertise in five areas — crop husbandry, agricultural marketing and value addition, social mobilization, law and accounts, and IT [10]. With funding from IAs, CBBOs are expected to mobilize farmers, train farmers and FPO staff, prepare business plans, ensure compliance, help FPOs apply for government schemes, establish market linkages, and possibly supply agricultural inputs and perform value addition. Each FPO has a Board of Directors (BoD) elected from amongst the FPO’s members. While the BoD determines the FPO’s overall direction and activities, the FPO is managed by a hired CEO and Accountant [10].

The 10,000 FPO Scheme establishes two instruments — the Equity Grant and Credit Guarantee Facility (CGF) — to address the capital constraints that characterize rural agriculture. The Equity Grant doubles an FPO’s total equity funding through a 1:1 match of equity up to Rs. 2,000 per farmer. A single FPO can get a maximum of Rs. 15 lakhs in funding and must have 300 members to be eligible. The Grant is paid out in tranches, so an FPO with 300 members (with Rs. 2,000 of equity each) could receive a Rs. 6 lakh grant in Year 1 and a Rs. 9 lakh grant in Year 3 once membership increases. The CGF reduces lending risk for financial institutions lending to FPOs. Under the CGF, NABARD guarantees 85% of the loan amount for loans below Rs. 1 crore and 75% for loans between Rs. 1 and 2 crores [10]. Outside of these two mechanisms, the scheme also provides funding for the formation, incubation, and management of FPOs. However, most of this funding goes to CBBOs and the professionals hired to manage the FPO.

Coupled with the activities of CBBOs, these capital delivery mechanisms have the potential to address many small farmer challenges. However, it is important to note that the majority of FPOs remain outside of this policy framework — only 23% of the FPOs registered by 2023 were promoted through IAs [11]. Most remaining FPOs were formed independently by groups of farmers. Relying heavily on a centralized policy structure risks ignoring this population.

A wide range of other agriculture schemes involving marketing infrastructure, the cultivation of specific crops, organic farming, and export-ready production have also been extended to apply to FPOs [12]. Additionally, the 2018-19 Budget announced that FPCs would be exempt from paying Income Tax [13]. However, FPCs still have to pay a 15% Minimum Alternate Tax on profits [14]. While many important policy components are in place, the policy landscape is hard to navigate for FPCs that lack technical and policy expertise.

Amul: The Gold Standard

Amul comprises 18 member unions that cover 18,600 villages and 36 lakh farmers [15]. Recognized in August as the strongest food brand in the world [16], it is arguably also the most successful agricultural collective. Several key factors contribute to Amul’s success. Among agricultural products, milk is unique. There are standardized processes for production and processing, accurate and low-cost checks for quality testing, and continuous daily production throughout the year. These characteristics have let Amul (and several other large dairy cooperatives) grow immensely without compromising on quality. The evenness and high frequency of production let farmers quickly understand the ease and benefits of working with Amul. Farmers’ consistent, frequent, and positive interactions with Amul contribute to a strong sense of ownership and buy-in.

Another crucial element of success is the separation of production and marketing. Village Dairy Cooperative Societies and District Milk Unions handle procurement, aggregation, quality testing, and value addition. The State Milk Federation is exclusively responsible for branding, marketing, and distribution. Thus, the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) — Gujarat’s State Milk Federation — is the marketing organization for the dairy cooperatives of Gujarat. GCMMF is India’s largest food marketing entity and generates $7.3 billion of annual turnover [15]. Most importantly, 85% of sales revenue goes directly to farmers [17].

FPC Performance

While Amul is based on a cooperative structure, its goal is the same as an FPC — creating a collectively-managed organization that increases farmer income and wellbeing at scale. How do FPCs stack up?

There is a dearth of good, publicly available data about FPCs at a national level. However, two metrics — strike-offs and paid-up capital — can help us understand performance. An FPC can be struck-off for three reasons — failure to commence operations within a year of registration, failure of members to pay the capital they committed, and not carrying out any operations for a period of two financial years. In 2021, 45% of FPCs that were 7 years or older had been struck-off [18]. In Maharashtra, the state with the most FPCs, only 16% of FPCs were found to be active [19].

Paid-up Capital (PUC) refers to the amount of equity capital that the FPC has raised from its members. For FPCs, membership fees (and the equity grant) are the only sources of paid-up capital. While the average PUC for all active (not struck-off) FPCs was Rs. 8 lakhs, the median PUC was Rs. 1 lakh. For 57% of FPCs, PUC was Rs. 1 lakh or less [18]. This reflects a highly skewed PUC distribution — the top 20 FPCs accounted for 44% of total PUC. Intriguingly, 13 of these 20 FPCs were milk producer companies [18]. Low PUC suggests that FPCs struggle to get farmers to join and pay a membership fee. It also means that most FPCs have inadequate funds to commence operations or provide meaningful value-addition.

Although FPCs were designed to address the capital access and member engagement issues that plagued cooperatives, the same problems persist. Consequently, most FPCs struggle to get off the ground. Without capital, FPCs can’t perform their intended functions — buying inputs in bulk, aggregating produce, and linking producers to the market.

Discussion

Like with many national-level schemes and policies, FPO policy has understandably focused on broadening coverage. However, creating FPCs that include lakhs of farmers is a waste of funding and resources if they fail to meaningfully improve farmer wellbeing. What are the primary challenges?

FPC registration is driven by a CBBO or group of farmers deciding to start an FPC in an area. Here, independent FPCs struggle to complete complex registration procedures, pay various fees, and create realistic business plans [20]. Since CBBOs tend to be NGOs, even they struggle with the business side of FPC incubation. Contrast this with Amul, where dairy farmers just complete a straightforward registration process for a village-level cooperative. Those cooperatives are then linked to a national-level marketing company through a clear structure.

Next is farmer mobilization — convincing hundreds of farmers to join an FPC and pay a membership fee. Although central recommendations suggest that FPCs should have at least 500 members, average membership is 222 [7]. Without a critical mass of members, FPCs struggle to gather both funds and scale. Once an FPC has members, convincing them to sell to the FPC is also challenging unless clear price increases are provided. Conversely, the early Amul cooperatives were formed with strong buy-in from farmers in response to exploitation by middlemen [21]. The price increases from eliminating middlemen started a virtuous cycle, with membership increasing as a result of increased compensation, further increasing economies of scale.

FPCs that successfully mobilize members and capital are typically able to perform input provision and output aggregation services, marginally increasing profits by reducing cost of cultivation and increasing the farm gate price. However, equity capital is usually insufficient to make the investments required to significantly increase income through value-addition and market linkage. This requires debt financing and government support, both of which have significant access and logistical issues. In Amul’s case, Operation Flood (“The White Revolution”) provided targeted infrastructure and capital that addressed every stage of the production process — inputs (cattle feed), production, procurement, processing, and marketing [22].

The extensive coverage of FPOs is promising. However, without initial capital and membership being nurtured by strong execution and management, FPOs will fare no better than cooperatives.

Bibliography

[1] A. Kanitkar, “The Logic of Farmer Enterprises,” Institute of Rural Management, Anand, Occasional Publication 17, Jan. 2016. Available: https://irma.ac.in/uploads/randp/pdf/1518_28072.pdf

[2] Ministry of Cooperation, “National Cooperative Database 2023: A Report,” Government of India, New Delhi, 2023. Accessed: Dec. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://cooperatives.gov.in/Final_National_Cooperative_Database_023.pdf

[3] Y. K. Alagh, “Report of High Powered Committee for Formation and Conversion of Cooporative Business into Companies,” New Delhi, Mar. 2000. Accessed: Dec. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.thehinducentre.com/publications/policy-watch/article32257842.ece/binary/26-Alagh%20committee%20report%20of%20high%20powered%20committee%20for%20formation%20and%20covering%20of%20corporative%20business%20into%20Companies,%202000.pdf

[4] T. N. Shah, “Farmer Producer Companies: Fermenting New Wine for New Bottles,” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 51, no. 8, pp. 15–20, Feb. 2016. Accessed: Dec. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298714452_Farmer_producer_companies_Fermenting_new_wine_for_new_bottles

[5] S. G. Patil, “Report of the High Powered Committee on Cooperatives,” Ministry of Agriculture, New Delhi, May 2009. Accessed: Dec. 27, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/hpcc2009new.pdf

[6] Tata-Cornell Institute, “FPO Platform for India.” Accessed: Dec. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://fpo.tci.cornell.edu/

[7] S. R. Thakur, “8875 FPOs have been registered across the country.” Accessed: Dec. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=2040845

[8] NABARD, “Farmer Producers’ Organizations (FPOs): Status, Issues & Suggested Policy Reforms,” 2020. Available: https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/careernotices/2708183505Paper%20on%20FPOs%20-%20Status%20&%20%20Issues.pdf

[9] Prime Minister’s Office, “Prime Minister launches 10,000 Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) all over the country.” Accessed: Jan. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pib.gov.in/pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1604743

[10] Department of Agriculture, Co-operation & Farmers’ Welfare, “Formation and Promotion of 10,000 Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs): Operational Guidelines,” Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, New Delhi, Jul. 2020. Available: https://dmi.gov.in/Documents/FPO_Scheme_Guidelines_FINAL_English.pdf

[11] Department of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, “Annual Report 2023-24,” Government of India, New Delhi, 2024. Available: https://agriwelfare.gov.in/Documents/AR_English_2023_24.pdf

[12] Department of Agriculture & Farmers’ Welfare, “Draft of National Policy on Farmer Producer Organisations,” Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, New Delhi, Jun. 2024. Available: https://agriwelfare.gov.in/Documents/HomeWhatsNew/National_policy_onFPOs_18Jun2024.pdf

[13] NABARD, “Handbook on Maintenance of Accounts and Preparation of Financial Statements for Farmer Producer Organisations,” Uttarakhand Regional Office, Dehradun, Mar. 2018. Available: https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/tender/0702203643FPO%20ENG.pdf

[14] S. N. S. Tomar, “Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 400,” Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Dec. 2023. Available: https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/1714/AU400.pdf?source=pqals#:~:text=Under%20Companies%20Act%3A%20Under%20section,section%20115JB%20(MAT%20provision).

[15] Amul, “Organisation.” Accessed: Jan. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://amul.com/m/organisation

[16] Economic Times, “Amul Emerges as World’s Strongest Food and Dairy Brand.” Accessed: Jan. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/cons-products/food/amul-emerges-as-worlds-strongest-food-and-dairy-brand-topping-global-rankings-in-brand-finance-food-drink-2024-report/articleshow/112676121.cms?from=mdr

[17] ET नाऊ, “Amul vision is to be the biggest dairy in the world; already exporting to almost 50 countries: MD,” The Economic Times, Mar. 12, 2024. Accessed: Jan. 04, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/markets/expert-view/amul-vision-is-to-be-the-biggest-dairy-in-the-world-already-exporting-to-almost-50-countries-md/articleshow/108426991.cms?from=mdr

[18] R. Govil and A. Neti, “Farmer Producer Companies: Report II, Inclusion, Capitalisation and Incubation,” Azim Premji University, Bangalore, 2022. Available: https://cdn.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/media/publications/downloads/report/Farmer_Producer_Companies_Past_Present_and_Future.f1597749327.pdf

[19] P. Biswas, “Only 16% of registered Farmers Producers Companies active in Maharashtra, reveals survey,” The Indian Express, Dec. 06, 2022. Accessed: Jan. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/pune/only-16-of-registered-farmers-producers-companies-active-in-state-reveals-survey-8307830/

[20] V. Nikam, H. Veesam, P. Chand, and K. T M, “Farmer Producer Organizations in India: Challenges and Prospects,” Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi, Oct. 2023. Available: https://niap.icar.gov.in/pdf/pp40.pdf

[21] Amul, “History - AMUL Dairy.” Accessed: Jan. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.amuldairy.com/history.php

[22] Amul, “A Note on the Achievements of the Dairy Cooperatives.” Accessed: Jan. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://amul.com/m/a-note-on-the-achievements-of-the-dairy-cooperatives

[23] Photo Credit — Isha Outreach.